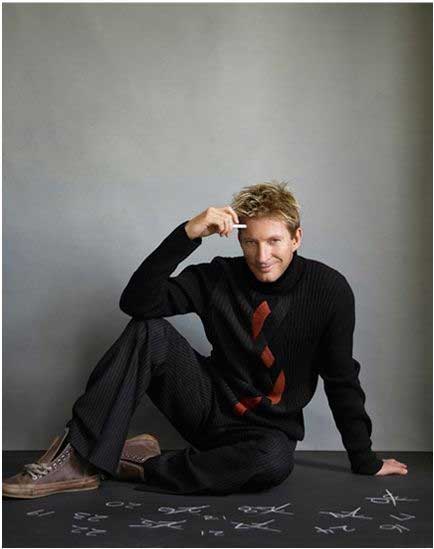

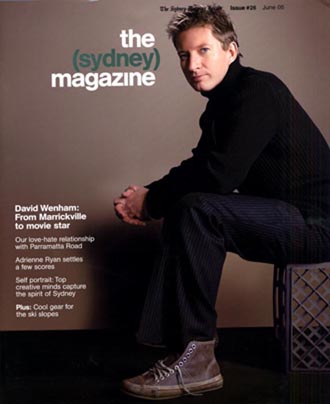

With his eclectic choice of roles, David Wenham continues to confound attempts to "read" his character. Angela Bennie meets one of Australia's most enigmatic actors.

He is wearing a black, V-necked pullover, his sharp face a slightly pockmarked, pasty creamy-yellow above it. His scraggly red beard is clipped unevenly and carelessly to the jaw-line; his unkempt, spiky hair is the colour of chopped straw. There is a strange stillness in his body, but the eyes, they are what hold you, pools of innocent sky blue, gazing almost blankly out at the world around him. It is very difficult to look away from those pools of blue. Meet David Wenham, actor.

At least, meet David Wenham, actor, as painted by artist Adam Cullen in his 2000 Archibald prize-winning portrait of him in the role of the notorious killer and rapist, Brett Sprague, in the film The Boys.

Or could it be a portrait of David Wenham, aka Diver Dan, "the thinking woman's crumpet", the heartthrob in the ABC television series, SeaChange, a role that launched the shy Wenham into the stratosphere of national celebrity?

"Definitely captures the spirit of Diver Dan," said a delighted fan, happily standing before the portrait at the Archibalds that year.

"Definitely not the adorable anti-hero of SeaChange," pronounced a learned critic.

It is one thing for an Archibald prize-winning portrait to cause controversy - this is par for the course for the Archibald. But it is not the debate about the execution of the work that is interesting here. Something else takes precedence and that something might be called the "Wenham factor".

This is the public's and the viewer's constant attempts to "read" Wenham, his character and personality, the need to seek out and grasp some essence perceived to be there in this portrait of him. This is what is intriguing.

And, given the startlingly conflicting accounts, it is clear he eludes their every attempt.

"I suppose the portrait looks quite normal, straightforward, just like David does," says Adam Cullen. "Or like he presents himself to be. But it is what is not there, what is absent, what he has put aside in reserve, that is what holds you. Definitely with him, it is what you are not allowed to see; that is what gives you the experience of intense presence with David."

Now here he is, in another gallery, in the flesh, sitting at a corner table on the mezzanine level of the National Gallery of Victoria, eating a salmon salad roll. The gallery's famous internal waterwall flows down in silent eddies on his right and to the left, beneath the mezzanine, are the still figures of the internal sculpture gallery. The space is quiet, restful, like Wenham, at ease in his chair. He has chosen this place for our interview.

The carrot-coloured outcrops of hair have been freshly spiked, the familiar, sharp-featured face is soft, almost gentle with goodwill, there is the faintest blur of red stubble on his chin. The sky-blue pools are neither blank nor innocent: they smile, they gleam with intelligence and humour, but there is just enough scepticism in them to make one wary.

"Very disruptive," he is saying. "Oh, yes! Very disruptive! Just stupid things I'd do, like taking off the teacher in the class when he had his back turned, that sort of thing. You could say I spent more time out of the classroom than in it."

He takes a bite of his roll. He is talking about his childhood in Marrickville, his restless high-school days with the Christian Brothers in Lewisham, remembering the silly pranks, the take-offs, the fooling around he used to get up to in class. No wonder his eyes are gleaming in the retelling; it is clear he enjoyed every minute of his time as an anarchist.

He was so bad, his mother insisted he had contributed to one of the poor brothers having a nervous breakdown and leaving the brotherhood.

The youngest of seven children, with five older sisters and one older brother, Wenham was clearly a problem, but a dearly loved one. It was a close family - "we didn't have much money growing up. We lived in an environment where there was no need for anything other than friendship and support within the family and the community for happiness. It was as simple as that," he has said elsewhere.

Restless, clearly intelligent; what to do with him?

With his love of impersonations and his ventriloquial skills, some of his energy was harnessed into the occasional shows he and one of his sisters would put on in the family dining room, charging two cents a ticket.

"They were puppet shows, mainly," says Wenham.

"My sister would be both box office and usher, and I would get behind the table and do the puppets. The whole family was the audience."

If the weather was good, he would file his pliant audience out into the backyard, lining them up on chairs in front of the small window of the backyard shed - and on with the show, the small window a perfect framing device for his puppets' antics.

And at school one of the teachers allowed him the occasional gig of 10 minutes in front of the class, doing his impersonations. He would take off whomever he so pleased: teachers, television personalities, pollies. "I was good at Gough Whitlam; I used to love doing Gough Whitlam," he remembers with a grin.

The teacher also suggested he might be interested in joining the school's Saturday-morning drama class. Which he did: he played Hotspur in the school's production of Henry IV, he wrote and performed his own ventriloquist show to tour with the school band - he was in seventh heaven.

His father was a wise man. Although the world of the theatre was not familiar to him, he could see the transformation those Saturday drama classes had made in his youngest son. As a birthday present he bought a subscription to the Genesian Theatre in Sussex Street, in the city, and began taking him in on the bus to the matinees there; later he expanded their horizons to what was then the Nimrod, now Belvoir Street Theatre, taking the boy across the city to the Nimrod's Sunday-afternoon matinees.

Young Wenham was enthralled, especially by those matinees at the Nimrod. "There was something about walking into the foyer of that theatre. That became my ambition, to perform on that stage one day."

As he now looks back on those weekend excursions with his father, Wenham shakes his head with wonder.

"My parents weren't people who grew up going to the theatre, they had no real knowledge of theatre, so how they knew that it might be something that would interest me, I don't know.

"But they saw that, and nurtured it and nourished it. I can't thank them enough."

Now in his 80s, his father still takes himself off to the matinees, Wenham says. "He still subscribes, he travels in on the bus to the Wednesday matinees at the Sydney Theatre Company. He may possibly be the only male in the audience, the day he goes."

As his high-school days drew to a close, Wenham tried for NIDA, but failed to gain a place. Fortunately for him, the University of Western Sydney had just started a tertiary drama course at Theatre Nepean. Wenham tried for that and was accepted into the first intake. It was 1984 and Wenham was 19.

And so begins the rise and rise of David Wenham, actor.

Wenham probably would not see it this way, as some kind of linear ascent. More of an expansion horizontally, a constant widening of possibilities and challenges, a search for roles that would create those challenges for him, test him out, push him.

Which is perhaps why the range of characters he has played over the 15 years or so of his professional life has been so eclectic, so extreme in their differences.

He is hard to categorise. From the aforementioned killer Brett Sprague of The Boys and the sweet-natured Diver Dan, Wenham has played everything from a Belgian priest (Molokai: The Story of Father Damien) to a heroin addict with the worst mullet haircut in the history of the universe (Gettin' Square, for which he won the 2003 AFI award for best actor), a strange bank teller (Idiot Box) to the legendary noble Faramir in The Lord of the Rings, a pyromaniac (Cosi) to, of all things, a sperm donor (Simone de Beauvoir's Babies, for which he won his first AFI best actor award).

A few months ago, you would have found him in one of the greatest roles the theatre has to offer, Rostand's Cyrano de Bergerac, at Melbourne's Southbank for the Melbourne Theatre Company, a role in which he has to dominate the stage for three hours of great drama, sublime comedy, swashbuckling swordfights and heartbreaking poetry. "A dream Cyrano," the critics crowed, with words like "charismatic", "mesmerising," "spectacular" falling off the review pages of the daily papers.

In his recent film, the Australian-made Three Dollars, Wenham plays the quietly desperate suburban husband and father Eddie, an "ordinary" man cloaked in painful bewilderment and almost the antithesis of the romantically heroic Cyrano.

"Wenham slips so naturally into Eddie's skin it's almost eerie," said the Herald's Sandra Hall of his performance. Another critic says it is as if Wenham has "channelled the spirits of Gary Cooper and Jimmy Stewart" onto the screen. Film writer Jim Schembri concedes that Wenham is an actor whose versatility "stretches to all points of the acting compass," but that here, as an Aussie everyman, "he is at his most impressive, exuding a quiet dignity that is as palpable as it is subtle".

But the next time you will see him, he will have turned all that nice ordinariness on its head. About to be released is his malicious landowner, Eden Fletcher, in The Proposition, filmed last Christmas in 50-degree heat up around Winton in Queensland alongside the likes of Ray Winstone, Emily Watson, Guy Pearce and David Gulpilil, with a script by Nick Cave.

It is certainly a rather exotic world that Wenham moves in these days, one minute dressed in a cassock in a leper colony on a Pacific island, playing imaginary cricket with Peter O'Toole to while away the hours between takes, the next on the stage in suave polo sweater as Ivan in the classy Parisian hit Art, at Sydney's Theatre Royal.

Or then again, a few years ago you could have found him in Macedonia filming a strange western, Dust, alongside Ralph Fiennes, then swathed in mist in the South Island of New Zealand, preparing for yet another take in Peter Jackson's The Lord of the Rings.

His first job when he left school was selling insurance with the NRMA, which pleased his mother very much. You'll never go far as an actor, she warned him. "It wasn't until SeaChange that my mum finally stopped reminding me I should never have left the NRMA," says Wenham.

He would also occasionally call the bingo nights at the Marrickville Town Hall just to make ends meet, while studying and trying out for roles as a newly minted actor after graduation.

Looking at the list of more than 25 films he has now made here and overseas, the long and distinguished list of roles he has performed in the theatre and on television, it is hard to see him as the casual host of those Marrickville bingo nights, let alone someone who once might have looked forward to a lifetime of selling insurance for his living.

Yet perhaps not; there is something modest, ordinary, unpretentious about Wenham. It is as though he is signalling, with his soft voice and slightly withdrawn manner: "Hey, I'm no star!"

When asked if he has ambitions to join "the Oscar club" alongside his mates Geoffrey Rush, Cate Blanchett and co, he gives an emphatic "Oh, gosh no!" That is the last thing on his mind, he says. "I have no other goal than to do what I do well. Winning Oscars is not part of my thinking."

He lives quietly with his partner Kate Agnew and one-year-old daughter Eliza Jane in an apartment in Sydney's eastern suburbs; he likes walking in the nearby park; he likes reading the newspaper over a coffee in the local cafe. He wanders around the 'hood in old jeans and casual shirts - his is not the high-flying, all-black-and-bling-bling world of celebrity and wannabes.

When he is away on a shoot, he calls home daily; and, if possible, he will fly home every weekend, or arrange for Kate and Eliza to come with him, especially if it is overseas. "We try to be together as much as we can as a family, commute as much as possible. It is not exactly easy. Eliza hasn't got a frequent flyer card yet, because she's under two, but she's clocked up a few points in her short life."

As Adam Cullen said, he is a straightforward kind of guy.

But as Cullen also said, like he presents himself to be.

A very old friend and colleague of Wenham's, film director Robert Connolly, who has directed the actor in several of his films, including Three Dollars, says Wenham's "simplicity" is deceptive.

"There is an extraordinary intellectual rigour there at work in David on everything he does. He will dissect everything down to the finest detail. When you work with him, he knows how to tweak a performance in microscopic ways. He is able to perform to fine degrees, like a great concert pianist knows dozens of permutations of strengths on the pedal.

"David's like that. It won't matter how many takes we do, he always knows how to press down or ease off, even if it is to the infinitesimal degree to get what it is we are after. Sometimes we don't have to say what it is; he just knows. He even knows what lens we are using and adjusts his performance to fit."

Wenham himself says that from the moment he takes on a role, his mind starts racing. He will read the script, over and over and over, he will read every book on the subject, he will walk for hours in the park, thinking it out in his head, visualising each moment, what he has to do with the character and what he might do with it, where he might take it. He needs to see it in his head, hear it.

He arrives at rehearsal, says Connolly, thoroughly prepared. Connolly met Wenham way back in the early days, when he was production manager on the notorious staging of The Boys at the Stables Theatre in Kings Cross in 1991. The atmosphere in the dressing room "was a very dark place to go. He would physically get himself into a state to be able to do the show", Connolly says. It was an energy he did not particularly want to be involved in.

In a previous interview, Wenham confessed it was a very difficult process to get to the violent psychopath Brett Sprague. "At first I could not see his face, but I could hear him. I could hear the rhythms of his character, I could hear the speech patterns, and then I could visualise the way he moved. I started to get him. And then his look came. The way he looked. And I knew I had him."

This intensity, Connolly believes, is the way Wenham approaches everything he does, this commitment to his work, to his life. He keeps this intensity hidden as much as he can. "There is a reserved quality about him. It is like a choice he has made to reserve some part of himself from the world. He has worked out how he can be an actor and yet not have to reveal all of himself. There is a part of him he doesn't want the world to see."

Surprisingly, Wenham confesses that it was the role of Eddie of Three Dollars he found very difficult - not to find, but to play. "It is very difficult to play a 'good' man. Very difficult. I am less comfortable playing just the ordinary person than a character type. The thicker the mask, the more comfortable I am."

What fascinated Adam Cullen was Wenham's ability to absorb and take on any character and his ability to project "a powerful intensity in an extremely economical way, without an excess of action".

"All that intensity he has goes into the empty space around him. So you are aware of an absence, something you cannot get to. This is what is fascinating about him. He is in that space.''

Wenham dismisses all reported accolades with a squirm in his seat. He is clearly uncomfortable discussing his art, his private life, what others might say or think of him. He is just doing a job he loves, he says.

"My school motto was conanti corona, a crown for the trier. That's me. Let's just say I try. I try."

The interview over, he puts on his sunglasses and exits the gallery's quiet through glass doors out into the bustle of the street. He disappears, an ordinary man dressed in sunnies and jeans, among the strolling couples along Melbourne's St Kilda Road.

"After the portrait was completed, I showed it to him," says Cullen. "He sat in silence for quite a long period of time. And then he said I had caught a part of him no one has ever seen before. What that was or what he meant, no one will ever know."

From here.