David Wenham’s unassuming but unswerving commitment to his craft has accelerated his star trajectory from calling bingo to calling some shots of his own. By Alex Graig.

David Wenham is the lobby of the Rockman Regency hotel in Melbourne. He sits in a lounge chair, legs outstretched, his left arm draped over its curved back, his head cocked, sky-blue eyes staring into space. He has the fair skin of a straw-berry blond, with a one-day shadow that threatens to turn ginger. He is beautifully dressed in a black suit with an open-collared electric-blue shirt.

He isn’t waiting for anyone and he isn’t going anywhere. He’s trapped at this minute waiting for photographs to be taken for this magazine while four people watch him, waiting.

Right now, Wenham is the centre of our universe, and this might just be his own personal version of hell.

But David Wenham simply isn’t there. He’s still, silent and it seems he’s slipped away somewhere.

This is the first time I have met the actor and I have expectations. Expectations that he will be like

SeaChange’s Diver Dan, the multilingual gourmet chef and ferry captain, the role, which launched him with laconic nonchalance into Australian’s consciousness. This might be unfair but I’ve been told by a friend of his that the best way to describe the 34 year old is as a “civilised larrikin”, a term that fits the sensitive but blokey Diver.

“David brings that laconic character humor to everything he does and he’s like that in real life”, confirms director Jonathan Teplitzky, who says he wrote the new film

Better Than Sex with Wenham in mind. “I just really like the laconic atmosphere that follows him”.

I’m expecting garrulous, I’m expecting laughter laden with thick lashings of irony. I’m limbering up for a session of mental backslapping. But this is not what happens at all.

You see, Wenham has the flu. And as such, I’m left with a disappearing act as Chinese medicine shoots him from the grip of fever to the Twilight Zone.

Still there’s something about the man, even when sick and washed-out, that’s remarkably true. He wins me over a simple ‘hello’ because of the way it springs out. It’s like he’s just been startled awake by life, his blue eyes widening. Wenham looks you in the eye, shakes your hand and then steps back. Left trailing in his wake is a kind of bemused graciousness that just hangs about like a cloud.

Ostensibly we are here to talk about

Better Then Sex, Wenham’s new film in which he stars as Josh, a wildlife photographer who embarks on a one-night stand with Cin (Susie Porter) and finds it processing to something deeper.

As the title suggests, much of the film takes place in bed, which is where he might like to be right now. Sleeping.

He seems shell-shocked to find himself now headlining films such as

Better Than Sex, the Australian thriller

The Bank and heading off to New Zealand to appear in Peter Jackson’s adaptations of Tolkien’s

Lord Of The Ring trilogy – which may just catapult his star to supernova status.

More than once and in vague wonder, he says, “I’ve found myself in a situation I never would have envisaged – which is playing a leading man. It’s not something I ever desired or saw myself doing, so it’s a great surprise for me”.

The actor who first made a name for himself in character roles such as the pyromaniac Doug in Cosi (1996) and a geeky straight player to Geoffrey Rush’s kook in

A Little Bit Of Soul (1998), is now the star attraction, buoyed by roles in

SeaChange (1998, TV),

The Boys (1997) and a rush of new films. But, here today, he’s not playing the star.

There’s no need to present his life like a story which Hollywood as the ultimate happy ending (clearly it’s not). No desire to contemplate the vagaries of fame. “It’s not like I’m Princess Diana”, he says ironically.

Unfortunately, because he is ill, he presents like life carries him along down the river, and occasionally he bobs his head up to check out the view. While Wenham says he always wanted to be an actor, he never “gave much thought” to how you make a career out of it. He just persisted. While directing a film with the help of his great mate Robert Connolly (who produced

The Boys and director of

The Bank) is a “plan”, the rest of his career is not his to own.

“It’s a hard thing to do”, he says. “You’re in the hands of the gods in this profession”. Fair enough, but I push a little further. Surely there are roles you’d like to play... He squints. “I’m sure there are but they haven’t come to the forefront of my focus at the moment. I wish that one would because I’ve been asked that question a lot. I can’t think of what it is”.

Eventually I ask, are you happy? “Yeah, yeah can’t complain...” he replies, looking at me. How? He shifts his weight on the couch, before offering. “It’s a combination of a whole lot of factors.

I’m normal really. I’m happy, other times I’m frustrated, other times I’m extremely upset – I’m normal.

I run exactly the same gamut of emotions as anyone else.”

And that’s just it. He’s normal, and that’s what makes him so likeable. He helps the photographer carry his equipment down to the lobby, even thought he’s running a fever. He endures endless photo set-ups in varying states with easy-going cooperation. He is polite to the last, and answers every questions put to him.

Yet, yet... I’ve spent three hours with the man and I have absolutely no idea who he is.

The youngest of seven, Wenham grew up in the cultural melting pot of Marrickville, Sydney and attended Christian Brothers, Lewisham. He was a brat he says, and probably somewhat better at pretending to be a B-52 bomber that a conscientious scholar. “I’d impersonate people a lot. I don’t do it any more. I’d impersonate fellow students and teachers – I’d mimic them for a few cheap laughs. I used to spend a lot of time outside the classroom: I was constantly kicked of class.”

In the case of the Film Appreciation class, the ban was permanent. “One day the guy who was running the course just stopped and just said, ‘I can’t take this any longer. Mr Wenham, just tell me, what is the name of the film that we’re watching?’ I had absolutely no idea and the guy next to me was trying to help me out and whispering, ‘The Dam Busters, The Dam Busters.’ I didn’t hear him correctly and I honestly thought the said ‘The Ten Bastards’ and I sad ‘Sir, The Ten Bastards’, quite proud that I knew exactly what we were viewing. I was kicked out of the rest of the semester. I was 13. I didn’t realise at this stage exactly what I was missing out on. I really was a young 13 years old,” he says ruefully.

Wenham’s home life was a happy one, and he always had a rich imagination. “There are images from my childhood that stick”, he recalls. “Sundays were great times in our growing up years. We’d always go somewhere and always by public transport. I grew up in a house with no car and, with seven kids, it was always a little journey. Sometimes they could be very simple things like just going for a walk – we’d love that as long as it wasn’t too far ‘cos our legs were always smaller than our father’s.

“One of the best memories I have as a kid was just walking around to the next street. There was a park that seemed extremely exotic. If you go back to it now Marrickville, it seems like quite a sad park but at that time, just that childhood imagination endowed it with so much more. I must have been about six I suppose and my mother was just picking leaves off this tree and the colours were just so vivid and I can remember what it was like...”. He adopts the tone of blue-rinse grandma, making light of the moment, “That’s one of my faaaavourites.”

Then his father started talking Wenham and one of his five sisters to Genesian Theatre matinees every Saturday. “That little theatre was like a bit of magic for me. Looking back on it now, it probably wasn’t brilliant but at that stage I thought it was incredible and we’d see things like Agatha Cristie-whodunit plays which I found horrendously terrifying at the time, and it was always a surprise as to exactly who did it.”

His father, sensing his son’s interest, started taking him to the Nimrod Theatre, which in the mid –‘70s under Richard Wherrett and John Bell, was a crucible for innovative theatre and new Australian writing.

“It was a revelation for me. John Bell was heading it. All the icons of the ‘70s – if they weren’t in Melbourne – they were at the Nimrod. And that really did have a huge impression on me.”

From there on, Wenham wanted to act. Shortly after finishing school, he left a brief stint as an insurance clerk and tried out of NIDA. He was eliminated in the first round but got into Nepean’s first intake for its new theatre course.

“My parents were always supportive,” he says quietly. “But they thought it was probably a foolish career choice ‘cos not many people make a career out of acting. I never thought about it. I just thought, “Oh yeah, that’s something that I want to do’. But they’ve come around. I’m doing OK and they’re proud, and makes me happy.”

“Doing OK” is a characteristics understatement. His stature as a leading man is confirmed by the fact that these days he tends to get the girl. He is considered in the same breath as Willem Dafoe whom he replaced on Dust, and Ethan Hawke who was rumored to also have put his hand up for the role of Faramir in

Lord Of The Rings.

“I think it’s a terrific time in his career because he’s an actor who could have been pigeon-holed into the great character actor,” says Connolly. “In a film like

Better Then Sex and certainly in

The Bank, he’s taken that step where he’s just a leading man. They’re very different skills.

“A lot of character elements you can fall back in and you look at American stars, are always playing some element in themselves and depending on that star charisma to carry a film. David has star charisma to carry a film. David has made that step.

Better Than Sex is such a terrific performance, it’s a star performance.”

Wenham is like an atmosphere. He communicates complex emotions onscreen without emoting. In everyday life, there’s a powerful stillness about him. But it’s as opaque as the ocean on the calmest, sunniest day. There’s no struggle against silence. He doesn’t fidget or look away or ignore you. He sits with you, equal and self-contained, companionable. It’s admirable because it’s so rare to be able to hold it.

Silence is one of Wenham’s greatest tools as an actor. In

The Boys, he builds his performance on it. Without once raising his voice, he is terrifying as Brett Sprague, the manipulative killer who cajoles his brothers into abducting a woman off the street and murdering her. Wenham is unrecognisable in the role, so much so he wouldn’t let his mother see either the play or the film.

“With Brett, there’s a very uncompromising attitude to the use of stillness and silence,” says

The Boys director Rowan Woods. “I don’t think I’ve ever seen a performance where the audience is waiting for someone to speak. Daze [Wenham] uses it to great dramatic effect. He’s very strategic as an actor like that. But it’s also cunning in relation to the character of Brett who manipulates those characters around him and makes people nervous around him because of the way that he behaves and the way that he manipulates situations to his own end.”

Jonathan Teplitzky agrees whole-heartedly: “There’s a quietness to David’s acting which I think is really good. In

The Boys that quietness was used to great effect because it’s all about internal emotional things... So often that kind of character could be depicted in a demonstratively violent, loud kind of way.”

While someone like Tom Cruise, Teplitzky says, is a very physical actor, everything’s about running about the place, Wenham is the exact opposite. “The emotional core where the character comes from is inside him and it comes out just as violent and just as powerful but from a different place.” Wenham knows when to disappear into himself. He found the pool of hate which severs Sprague’s social, moral and empathetic connections with the world. His eyes, throughout, are lifeless.

Wenham thoroughly disdains method acting.

“That’s when acting becomes very dangerous,” he says.

“It goes into a form of psychotherapy, and that’s something I don’t subscribe to at all. People who say they’re so immersed in the character, that they become the character, I actually don’t believe them, unless they have a mental illness. I’m quite serious there...” he says intently, holding my gaze. “There’s a definite line between character and actor.

“You have to throw off the character, or it has an impact on your life. I did have that problem on stage [in

The Boys] for however long. You know, that character does rub off on you in a way, just [because of] the nature of the piece, the fact that it’s so draining and so raw. It has an effect, but it’s not something I turn into.”

I

It’s not until the following week when I meet Wenham again – back on earth in Sidney’s Surry Hills – that some things become apparent. We’re at the studio of a mutual friend, photographer John Webber and this time Wenham is chatty, friendly, and completely relaxed.

He reclines on the bed, a picture of health, despite the fact that three days after I last saw him he found himself in the Yarra at 3 am, freezing and surrounded by the city’s refuse.

The actor was wrapping his final scene for

The Bank in which, Wenham says, Melbourne is the “sexy star”, a futuristic financial megalopolis. Only he performed his final scene in what resembled a sewer. Plastic bottles floated past, along with other, unspeakable things. The film crew had to keep cutting to let it all flow by. And that’s when a tree, branches and all, drifted past.

There’s a Pythonesque side to Wenham. Throughout the afternoon he displays a highly developed antenna for the faintly ridiculous – veering into the downright hilarious. His recollections and anecdotes have a daffy loopiness. He sends himself up, und then tosses it off with a shake of the head, before spluttering with laughter. Life is a ludicrous thing.

Let’s call these moments Wenhamisms. A typical Wenhamism goes like this: when he was studying at Theatre Nepean’s drama school some 15 years ago, he lied about his age but only tracked on a year, “just sort of to be more mature,” he says, pronouncing it

ma-chewer, all ocker-like.

“It was only one year that was what was embarrassing. When I was 20 all the fellow students gave me 21st present and that was fine at the time, but 12 months late when I was really 21, my parents were throwing a 21st birthday party and wanted to invite all the students I was going to college with.

“Eventually I had to fess up and that’s one of the most embarrassing moments of my life. Having to tell everyone who gave me 21st birthday a year before, that this year is really my birthday,” he says, laughing raucously, literally in stitches on the on the pavement where we sit. “Luckily they eventually cacked.”

So you received two lots of presents? “Yeah. God I’ve got good friends,” he says in mock wonder, and pauses. “Or did have”...

It strikes a suitably comic note that Wenham called bingo at Marricville, Town Hall to put himself through five years of drama school.

Connolly says: “There’s something quite mischievous about David and it’s not really tapped yet. In

Better Than Sex, he’s a funny character [but] I think he can pull off a Jim Carrey role. He’s got a slapsticky humour about him.”

Accounts from the set of

Better Than Sex suggest it was all a hit of a laugh with Wenham as ringleader. Teplizky tells of the bath scene where Josh and Cin recount their sexual history. It’s quite romantic. No so offscreen. There was a sausage Wenham kept from the breakfast scene which he floated out at an opportune moment. “There were lots of little moments along those sorts of lines where you know it’s just lighten the load all the time.”

“On set he has this incredible knack when things are really stressful and everybody’s working in a difficult situation to swing into this comic mode which is absolutely hilarious,” says Connolly of Wenham on

The Bank. “I saw the comic banter between him and Anthony LaPaglia. It made me think there’s a fantastic comic role out there for him. He’s a very very funny man.”

Wenham once has to write an essay on the difference between nude and naked as one of the components of his theatre course. It’s one of his many punchlines in the game of life. This essay may have stood him in good stead because in

Better Then Sex he spends a lot of time nude. But in

When Harry Met Sally-style interviews to camera (fully clothed), they chart the course of their relationship. There’s a moment when Wenham talks about love, thinks on it, comes to a place inside that’s rarely visited and, for a second, he is utterly naked.

There are hidden depths to Wenham, I know, but mostly they’re out of reach. Asking which of his characters he is most like, he is most like, he comes back with “Brett Sprague,” not missing a beat before ripping into a wicked laugh. “No, actually, that’s a difficult question. Well you know the obvious answers are the roles like

Better Than Sex and Diver Dan and whatever but they’re not as well... I’m much stupider than any of those people.”

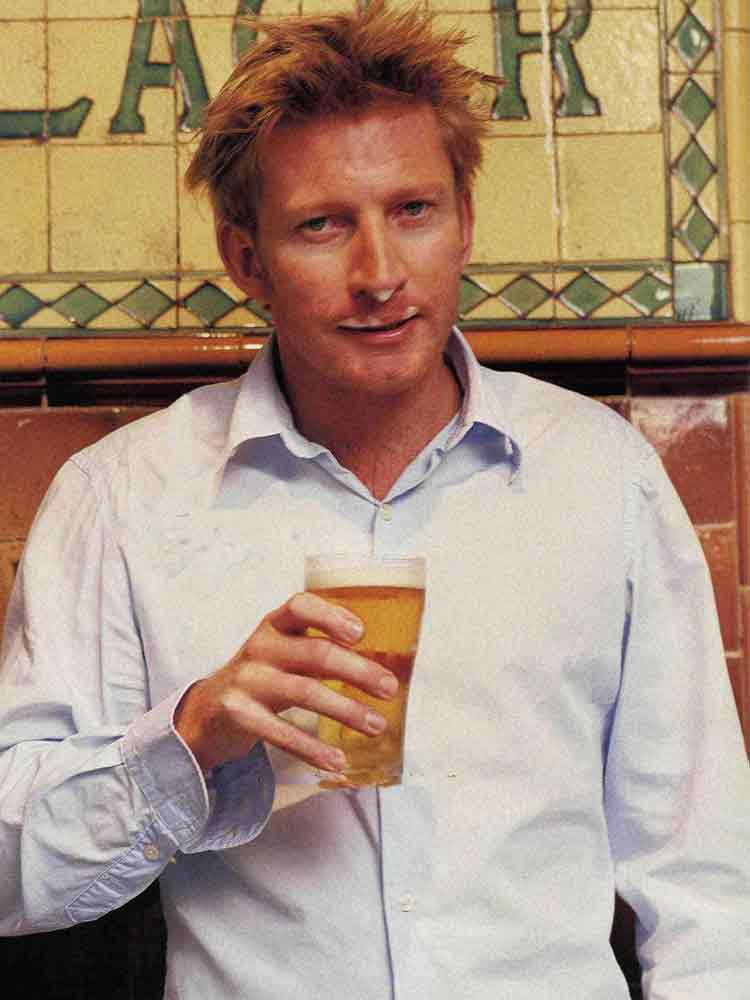

He prefers the role of observer, rather than subject. It’s habitual. Later at the KB Hotel in Surry Hills with photographer Webber and two others, Wenham drifts more than once. He quietly sips his beer, watching the old codgers stake out their territory on their favourite stools and regular corners. Wenham, a small smile tugging at his face, is enthralled.

In Melbourne, I asked him where else life could have taken him. “I’ve never had another career so I don’t know,” he replied. “I’ve often thought about what [else] I’d like to do and the only thing I can think of, is... there’s a man who works in the park opposite where I live and he cuts the lawn and tends the gardens every day. And he seems to live such a happy existence, I think ‘ah, maybe that’s what I’d like to do,” he’d said, a little wistfully.

More than once I find myself thinking, don’t let this man become too famous. Offscreen, he’s most happy when all eyes are anywhere but of him. Five rounds of VB and still he rarely rakes the floor. Instead Webber regales us which stories of their exploits together – surreal photo shoots at the club Dancers downing vodka crushes. Wenham just laughs, shakes his head and splutters.

Suddenly they both think it would be hilarious if we took some shots outside the pub right this minute: Wenham, nose in beer; Wenham, froth on nose. He saves the best to the last shot. He takes a huge swig – mouth full, all wide-eyed innocence, he suddenly projects it across the pavement. It sounds gross. But, because Wenham harvests joy from every moment, it’s actually endearing to a girl who’s stumbled into a boys’ night out. He flies headlong into the ridiculous without fear.

Fame and contemplating his potential market share of ‘sex symboldom’ don’t really take up much of Wenham’s mental energy. I ask the question, he looks bemused and a bit vague. “I don’t see myself as your Hollywood mainstream actor at all.”

“He’s smart enough to know that fame alone doesn’t amount to much,” says Teplitzky. “I think he’s one of those people who knows that it’s about doing good work.”

There’s a fearlessness to his choice of projects. Wenham has played the lot, from a saint in Paul Cox’s

Molokai: The Story Of Father Damian (1999) to a gun-slinging American in the new art-house European film

Dust (2000). He’s pushed the bounds of acceptance with the character of Brett Sprague.

“You can see it in all Dazey’s work,” – Wood says. “He really goes for it. If Dazey’s going to fail at anything he’ll fail gloriously and I love him for that, not just as a director but as a fun of movies.”

Like most actors, Wenham knows the buzz can evaporate in an instant. “There hasn’t been a moment where I’ve felt comfortable because I’m always aware that it could all finish tomorrow,” he says. I’m surprised because he’s dead serious.

“I’m very aware of the nefarious nature of the industry. I’ve never wanted to become complacent about what I do or where I’m heading.

“Somebody said to me the other day ‘it must get easier – acting – as you get older. But I don’t think it does. I actually think it gets harder because there’s more expectation, there’s more pressure...

“I’m enjoying my thirties much more than my twenties undoubtedly. I’m more relaxed. And the strange thing is, the more I’m relaxed the better things become as opposed to trying to force them to happen.”

Spending time with Wenham is like standing in front of a carnival mirror making faces into the distorted glass, seeing who can laugh the loudest and longest and come out making sense out of nonsense.

Wenham has that wonderful ability to simply be in the moment. It’s his great talent as well as his best disguise.

A Wenhamism goes something like this. One last request: describe yourself.

“That’s a shocking question. Oh God,” he says, shaking his head.

“I’m testing your adjectival skills.”

“My use of adjectives? Well that’s poor because I don’t read then Thesaurus as often as I should,” he says, playing deadpan to the hilt. “And I come across with adjectives like good and average and ok, you know average bloke, alright. How would I describe... How would I describe myself? I don’t know, I couldn’t do it with words, I’ll do it with a liturgical dance!”

He leaps up and launches into a number to which words may never do justice. Part ballet, part Riverdance, with the tone of a court jester, Wenham still manages to convey grace and a piss-take all at once. “So there you go,” he says, winding up. And then he just laughs and laughs and laughs.

Comic relief - one of the Wenham’s friends describes him as a “civilised larrikin” – equal parts lad who enjoys a pint, and total gentlemen.

Star turn – “It’s a terrific time in his career because he could have been pigeon-holed into the great character actor,” says Connolly.

Wild Thing – As a child, Wenham impersonated other people. In

Better Than Sex, this skin comes in handy impersonating the twitchy meerkat.

From here.