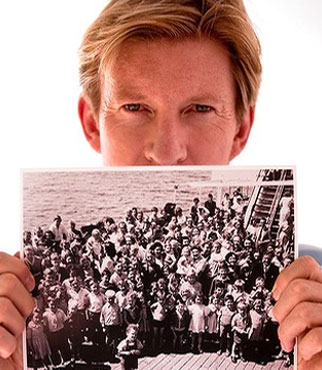

THIS debut feature film of director Jim Loach shines a light on an ugly period in British and Australian history in the ’50s and ’60s when around 7000 British children were deported to Australia. The kids were promised a land of oranges and sunshine but instead found themselves imprisoned in an institution where they were put to work as labourers and frequently abused. The film is set in the 1980s and follows social worker Margaret Humphreys (Emily Watson), who uncovered the heinous story for which the British and Australian governments officially apologised last year. Jim, son of acclaimed veteran direction Ken Loach, spoke to Luck Buckmaster about some of the many issues involved in making Oranges and Sunshine.

Oranges and Sunshine has generated a strong response from critics and, perhaps more importantly, from many people on a personal level. The person I was sitting next to while watching the film was reaching for tissues at the end of it and I’m guessing she wasn’t the only one, right?

There was a very interesting – kind of funny, but I’m not sure funny is the right word – article published here in the UK about how some of the screenings of the film were getting disrupted by excessive wailing. Obviously it’s something that many people have a strong emotional reaction to, which I’m glad about, because in the end the reason you make a film is for viewers to make a connection with the people on screen. Generally we’ve been so pleased with the way audiences have responded to it. They’ve taken it as a very inspirational story and that’s great because in the end it is uplifting because the people in it survived, against all the odds, but they survived. And that’s really heart-warming.

Given the real life events depicted in the film, the gravity of these events and the number of people who have been affected by what happened, this is a bold project for anyone to take on, let alone a first-time feature filmmaker. How did you grapple with that responsibility? Did you at any time doubt your ability to do the story justice?

It was something I thought about a lot. I think, if I’m honest, that when I first started to look at it I probably didn’t realise exactly what I was taking on. I didn’t take on board the enormity of it. It was a huge responsibility but it was too good a story to walk away from. Once I had heard about the story, and especially once I had met the people involved, I just couldn’t walk away from it. I felt like I had to do it, through hell or high water.

I found the story remarkable in the sense that it’s based on true events I had no idea transpired. I spoke about the film on the radio and reviewed it quite positively. During my review a gentleman called in whose father was taken to one of these institutions, which goes to show you how widespread the consequences of these events are. They say there were 7000 children shipped to Australia and about 150,000 internationally. How come so few people have heard about this?

It’s extraordinary, isn’t it? When we were making the film that’s what always gave us confidence in it. Whenever we started to talk about the story, people were amazed. Everybody had heard very little or nothing about it and found it incredible. That always gave us confidence that we were telling a story people would want to engage with.

One thing I didn’t get from the film – and I don’t mean this necessarily as a criticism – is the logic behind these events happening in the first place. Why were the kids exported and why under those circumstances? I am assuming that as a filmmaker you asked yourself these questions but didn’t want to go down the rocky road of speculation.

Yes, that’s true. Of course we looked at all of that during the scripting process. The truth is, as it seemed to us anyway, that because there were so many different reasons and motives at play it was very hard to encompass it all in one or two scenes and present it as a neat package.

Part of it was economic. For instance, Margaret Humphreys came across a document she still has, which was from the Home Office in Britain. They’d done the maths and a ticket from Liverpool to Sydney cost less than it cost to keep a child in care in Britain for a month. So part of it was just, honestly, less expensive, and they (the children) were seen as a burden on the state in Britain. There was a housing shortage here, too, post war. And Australia wanted children because during the 1950s and ’60s there was a phrase that was used – Australia wanted “good white stock”. There was a whole culture around – and it’s a horrible phrase – what was called the “yellow peril”, which was obviously the Asian country’s migrants coming from to Australia. So there were a lot of different reasons at play and there was also the whole missionary aspect to it. There were many different issues at play. The most obvious were economic and empire-building.

The subject matter in Oranges and Sunshine is dramatic and hard-hitting but your direction is very restrained in many ways. An example of how restrained your direction is, is particularly evident in a scene where the characters – played by Emily Watson and David Wenham – go back to the place where it all happened and have a cup of tea. The scene is subtle and measured. Were you not tempted to crank up the dramatic tension?

We were, absolutely. In fact we wrote lots of different versions of that scene. We needed to provide a climax to the film but we also wanted to be truthful – at least truthful in terms of the film that we were making. There isn’t ever a great moment in court when all the wrongs are righted, so we didn’t want to have a cop-out ending where it’s suddenly all OK. Rona (Munro, the screenwriter) wrote the script and came up with this idea of the characters having a cup of tea. Straight away we loved it, because it’s unexpected. We were excited because we felt we’d never seen that scene in the cinema before.

When you make a film like Oranges and Sunshine, which has such strong political undertones, you inevitably become knowledgeable in the subject and a magnet for discussions outside the realm of filmmaking. For example, your thoughts on politics. I’m interested to know your opinion on blame and guilt. The film doesn’t tell us who is to blame; it’s more sophisticated than that. But perhaps you can: whose fault was this? Do you level blame at the respective governments?

Yeah, I do, absolutely. Thanks for what you said. We consciously set out to not make a campaigning film. We wanted to make a film for audiences who knew nothing about this, were not on the radar, but just wanted to go to the cinema and be told a cracking story. That’s what we were aiming for, but as you say you inevitably get a lot of knowledge on the subject and absolutely — the buck stops with both our respective governments, I’m afraid.

Particularly, I would say, the British government because in the end they were British kids. The Home Office had to give its consent for every child leaving the country. In many cases it didn’t but it should have. They were British kids and it’s shameful that it took so long for the British government to acknowledge what happened. Secondary to that, they got very tough treatment in Australia and that’s where responsibility lied with the Australian government. I mean, the buck stops with the government, doesn’t it?

I don’t disagree with you, but when the politicians were signing these documents while doing a million other things, do you think they knew what they were doing? Was it primarily a case of negligence?

That part of it is really complex and that’s why we didn’t go into it in the course of an hour-and-a-half film. It’s really hard to speculate about motives. For instance, when the film was released here there was a lot of discussion in the press. It was suggested that some people must have been acting out of good motives, that they must have felt they were doing the right thing by the kids. That’s possibly the case. There’s no way of me knowing and I couldn’t say one way or the other. Some people probably did think they were doing it for good reasons. I personally find it very hard to believe that anyone who tells a child that their parents have died, when they know their parents are still alive, to think they are doing that for the best of reasons is difficult to believe. But there were all sorts of complex motives at work, absolutely. It’s hard to separate them out.

When I interview somebody in the film industry whose related in some way – professional or by blood or otherwise – I don’t think it’s right to shift the focus for too long onto another person, but at the same time there is an expectation of some kind of discussion. So talking just briefly about your dad, Ken Loach, who’s made some wonderful films – in recent years I particularly liked Looking for Eric – did he visit the set, or voice any strong opinions, or offer sage advice?

He does give me a lot of advice. We talk all the time; I’m very close to my dad. When we were in the cutting room, for instance, he popped in and gave me a few suggestions and certainly when we were putting the script together he gave me a few ideas. We talk all the time, and obviously to me it’s not really a big deal because he’s my dad. I don’t really know the person called Ken Loach, I only know my dad, if that makes sense.

You touched upon how the film was written and structured. One of the obvious ways to present the story would have been through flashbacks to when children were abused, tormented and made to work. More cliche perhaps, but it could have worked. Why didn’t the film tread that line? Why was it always based in a present-day 1980s, with the characters looking back?

We looked at flashbacks and at one point Rona wrote them and they were in the script but in the end we chucked them out because a) they told us what we already knew and b) they seemed sensationalist. More importantly, we felt that to be truthful to the story we wanted to explore how these people had come through what they experienced as children. How they had recovered from their experiences.

There’s a lot of impact when the characters look back and reflect. To me, the most interesting was the David Wenham character (he plays one of the survivors). It felt like his character’s spirit couldn’t be broken because it was smashed up and rebuilt many years beforehand. Does that make sense?

There’s a lot of impact when the characters look back and reflect. To me, the most interesting was the David Wenham character (he plays one of the survivors). It felt like his character’s spirit couldn’t be broken because it was smashed up and rebuilt many years beforehand. Does that make sense?

I think that character is absolutely fantastic and David just completely nailed it. It was a complete joy to see him bring that character to life. He has won a lot of hearts with his portrayal, so I’m really chuffed. What I love about David is that he has an incredible complexity going on underneath but he doesn’t like to play it every moment. He has a great sense of fun and joy and spirit about him, which I really, really love, and underneath that you can see a lot of complexity in terms of emotions and dilemmas and so on.

You said in previous interviews that when you were young you were adamant you wanted to become a journalist, not a filmmaker. Given that Oranges and Sunshine is based on real events, was this project some way of merging the two?

It probably was in a way, yeah. I was brought up to be very engaged in the world and outward-looking, so I suppose maybe my desire to be involved in journalism has come out through this.

You’ve done a lot of TV work. TV tends to be much quicker in terms of the shooting process and the turnaround. When you made the transition to feature filmmaking, what shocked or surprised you the most?

Gosh, that’s a good question. For me it was having complete control over the project. That was the most important thing for me, probably because I’m a complete control freak. For me, the core of it is what you want to say to the audience with your piece of work and what you want audiences to take away from it. So that was the biggest difference between my television work and the film.

So in other words, working in film has been much more fulfilling for you than working in television?

Yeah it has. It’s liberating.

From

here.